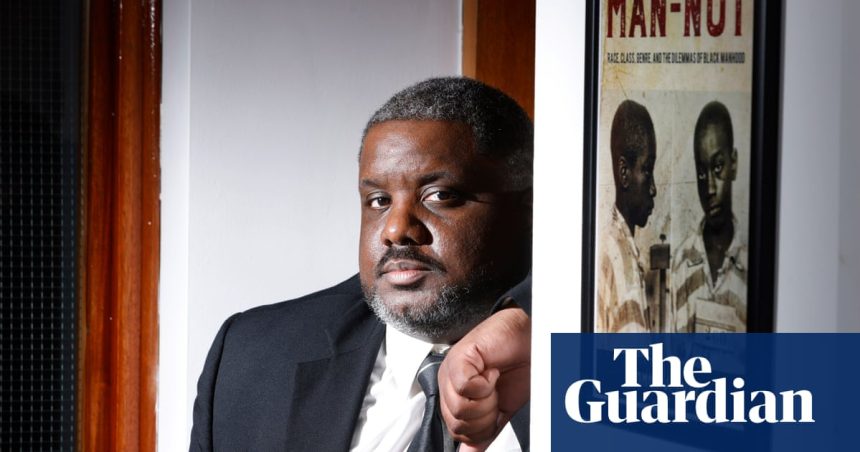

Tommy J Curry, the first Black philosophy professor in Edinburgh University’s 440-year history, sheds light on issues of institutional racism and historical connections to transatlantic slavery. The Louisiana native, who steered a critical inquiry into the university’s ties to slavery and the origins of racist biological theories, believes his appointment starkly illustrates the challenges ahead for the institution.

Curry suspects he may also be the first Black academic in the UK to spearhead a university investigation into its colonial and enslavement legacies. He aims to pave the way for future Black faculty, asserting, “I’ll be the subject of another report, but I won’t have influence.”

He emphasizes that the goal is not merely to produce a report but to catalyze change. “The real fundamental issue is change. Not a symbolic apology, not a pay cheque. [How] do you create leagues of Black thinkers and clinicians and doctors and engineers and artists… that fill the gap of what were lost by what white people engineered for centuries?” This vision, he notes, is critical for addressing deep-seated racial disparities in health, employment, housing, and education in Scotland.

Curry’s unique position within Edinburgh’s philosophy department, which has 12 tenured professors, highlights the report’s findings about the severe underrepresentation of Black staff and students. The report, co-chaired by Dr. Nicola Frith, revealed that less than 1% of the university’s workforce (150 out of 17,260 employees) identified as Black, a number that has remained unchanged for years. In contrast, the percentage of Asian staff saw a rise from 7% in 2018-19 to 9% in 2022-23.

The student demographic at the university also presents disparities. In 2022-23, 34% of undergraduates were Asian, mostly due to an influx of Chinese students, while only 2% were Black. Among postgraduates, 44% were Asian and 5% Black. The report notes that this increasing diversity has not translated into benefits for Black staff and students, despite Edinburgh’s claims of being a global institution.

According to 2021 Scottish census data, the non-white minority ethnic demographic stands at 7.1% nationwide, whereas in Edinburgh, it is slightly higher at over 15%, with 2.1% being Black. Curry contemplates the contradiction, stating, “Scotland is a free society… yet you have about the same percentage of Black people teaching here.”

Addressing the university’s potential, Curry argues for transformative actions, such as establishing a dedicated center for the study of racism, colonialism, and anti-Black violence. He also calls for a focused effort to recruit Black scholars and students, potentially funded through new scholarships.

Frith notes the report’s initiative to include Black and minority ethnic scholars with expertise in colonialism and reparations policy. Edinburgh has been a hub for reparations research for nearly a decade since hosting a pivotal conference in 2015.

The push for a comprehensive review arose from a collective response among staff and students after George Floyd’s murder in 2020 and the subsequent groundbreaking report from Glasgow University regarding its historical slavery debts. This growing momentum has further intensified discussions surrounding Edinburgh’s colonial history, especially regarding the controversial legacy of David Hume.

“I don’t see that history as something that sits in the past with a closed door,” Frith asserts. She and Curry contend that adopting the report’s recommendations could yield significant societal change. Curry concludes, “A center, an institute, the creation of Black scholars in the UK around this issue of racism, dehumanization, and colonialism is something that will change the intellectual tenor and academic climate of the country.”

As he envisions the university’s role in addressing its historical injustices, Curry states emphatically, “If the University of Edinburgh served as the pinnacle of the 17th, 18th and early 19th century for this work, why can’t it serve as the same center to undo it in the 21st century?”